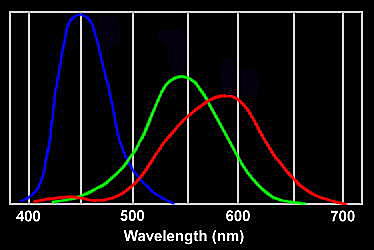

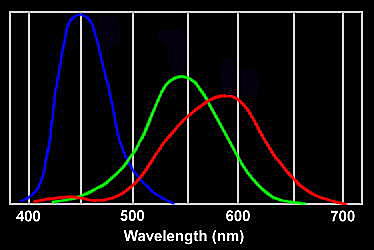

På øjets nethinde sidder tre forskellige typer af farvereceptorer. Receptorerne reagerer kraftigst på bølgelængder svarende til rød, grøn og blå hvilket gør mennesket i stand til at se farver.

Oversigt over det hvide lys' spektrum

|

Bølgelængde / mm |

Farve |

|

|

Ultraviolet |

|

0,000390 |

|

|

Violet |

|

|

0,000455 |

|

|

Blå |

|

|

0,000492 |

|

|

Grøn |

|

|

0,000577 |

|

|

Gul |

|

|

0,000597 |

|

|

Orange |

|

|

0,000622 |

|

|

Rød |

|

|

0,000780 |

|

|

Infrarød |

|

|

|

Undersøgelser har vist, at ikke alle typer stråling udsendes med lige stor intensitet. Således udsendes det violette lys kun med en relativt lille intensitet i forhold til de øvrige farver.

Det hvide lys fra solen er sammensat alle regnbuens farver, hvilket blev demonstreret af Isaac Newton. Newton benyttede et prisme til adskillelse af de forskellige farver og dermed vise farverne som et spektrum.

På øjets nethinde sidder tre forskellige typer af farvereceptorer. Receptorerne reagerer kraftigst på bølgelængder svarende til rød, grøn og blå

hvilket gør mennesket i stand til at se farver.

Hvorfor er himlen blå?

I dagslys er himlen blå fordi molekylerne i atmosfæren bryder det hvide lys fra

solen. Lys med en lavere bølgelængde brydes før lys med større bølgelængde. Når

himlen er blå skyldes det, at blåt lys har en mindre bølgelængde end rødt lys. Når man kigger

mod solen ved solopgang ser vi derimod de røde og orange farver, da det blå lys

er blevet afbøjet, længe før det når iagttagerens øje.

Som nævnt ovenfor udsender solen stråling med

mange forskellige bølgelængder, men også med forskellige intensiteter. Da det

violette lys udsendes med lav intensitet og en del af lyset ydermere absorberes

i atmosfæren, er den violette farve ikke dominerende på himlen.

En anden del af forklaringen er, at øjet er mindre sensitivt overfor den

violette farve, men hele forklaringen er ikke givet hermed.

I en regnbue kan den violette farve tydeligt iagttages, hvordan er det muligt, når den foregående forklaring tages i betragtning?

The spectrum of light emission from the sun is not constant at all wavelengths, and additionally is absorbed by the high atmosphere, so there is less violet in the light. Our eyes are also less sensitive to violet. That's part of the answer; yet a rainbow shows that there remains a significant amount of visible light coloured indigo and violet beyond the blue. The rest of the answer to this puzzle lies in the way our vision works. We have three types of colour receptors, or cones, in our retina. They are called red, blue and green because they respond most strongly to light at those wavelengths. As they are stimulated in different proportions, our visual system constructs the colours we see.

Response curves for the three types of cone in the human eye

When we look up at the sky, the red cones respond to the small amount of scattered red light, but also less strongly to orange and yellow wavelengths. The green cones respond to yellow and the more strongly-scattered green and green-blue wavelengths. The blue cones are stimulated by colours near blue wavelengths which are very strongly scattered. If there were no indigo and violet in the spectrum, the sky would appear blue with a slight green tinge. However, the most strongly scattered indigo and violet wavelengths stimulate the red cones slightly as well as the blue, which is why these colours appear blue with an added red tinge. The net effect is that the red and green cones are stimulated about equally by the light from the sky, while the blue is stimulated more strongly. This combination accounts for the pale sky blue colour. It may not be a coincidence that our vision is adjusted to see the sky as a pure hue. We have evolved to fit in with our environment; and the ability to separate natural colours most clearly is probably a survival advantage.

A multi-coloured sunset over the Firth of Forth in Scotland.

When the air is clear the sunset will appear yellow, because the light from the sun has passed a long distance through air and some of the blue light has been scattered away. If the air is polluted with small particles, natural or otherwise, the sunset will be more red. Sunsets over the sea may also be orange, due to salt particles in the air, which are effective Tyndall scatterers. The sky around the sun is seen reddened, as well as the light coming directly from the sun. This is because all light is scattered relatively well through small angles--but blue light is then more likely to be scattered twice or more over the greater distances, leaving the yellow, red and orange colours.

A blue haze over the mountains of Les

Vosges in France.

Clouds and dust haze appear white because they consist of particles larger than the wavelengths of light, which scatter all wavelengths equally (Mie scattering). But sometimes there might be other particles in the air that are much smaller. Some mountainous regions are famous for their blue haze. Aerosols of terpenes from the vegetation react with ozone in the atmosphere to form small particles about 200 nm across, and these particles scatter the blue light. A forest fire or volcanic eruption may occasionally fill the atmosphere with fine particles of 500-800 nm across, being the right size to scatter red light. This gives the opposite to the usual Tyndall effect, and may cause the moon to have a blue tinge since the red light has been scattered out. This is a very rare phenomenon--occurring literally once in a blue moon.

The Tyndall effect is responsible for some other blue coloration's in nature: such as blue eyes, the opalescence of some gem stones, and the colour in the blue jay's wing. The colours can vary according to the size of the scattering particles. When a fluid is near its critical temperature and pressure, tiny density fluctuations are responsible for a blue coloration known as critical opalescence. People have also copied these natural effects by making ornamental glasses impregnated with particles, to give the glass a blue sheen. But not all blue colouring in nature is caused by scattering. Light under the sea is blue because water absorbs longer wavelength of light through distances over about 20 metres. When viewed from the beach, the sea is also blue because it reflects the sky, of course. Some birds and butterflies get their blue colorations by diffraction effects.

Images sent back from the Viking Mars landers in 1977 and from Pathfinder in 1997 showed a red sky seen from the Martian surface. This was due to red iron-rich dusts thrown up in the dust storms occurring from time to time on Mars. The colour of the Mars sky will change according to weather conditions. It should be blue when there have been no recent storms, but it will be darker than the earth's daytime sky because of Mars' thinner atmosphere.

The spectrum of light emission from the sun is not constant at all wavelengths, and additionally is absorbed by the high atmosphere, so there is less violet in the light. Our eyes are also less sensitive to violet. That's part of the answer; yet a rainbow shows that there remains a significant amount of visible light coloured indigo and violet beyond the blue. The rest of the answer to this puzzle lies in the way our vision works. We have three types of colour receptors, or cones, in our retina. They are called red, blue and green because they respond most strongly to light at those wavelengths. As they are stimulated in different proportions, our visual system constructs the colours we see.

Response

curves for the three types of cone in the human eye

When we look up at the sky, the red cones respond to the small amount of scattered red light, but also less strongly to orange and yellow wavelengths. The green cones respond to yellow and the more strongly-scattered green and green-blue wavelengths. The blue cones are stimulated by colours near blue wavelengths which are very strongly scattered. If there were no indigo and violet in the spectrum, the sky would appear blue with a slight green tinge. However, the most strongly scattered indigo and violet wavelengths stimulate the red cones slightly as well as the blue, which is why these colours appear blue with an added red tinge. The net effect is that the red and green cones are stimulated about equally by the light from the sky, while the blue is stimulated more strongly. This combination accounts for the pale sky blue colour. It may not be a coincidence that our vision is adjusted to see the sky as a pure hue. We have evolved to fit in with our environment; and the ability to separate natural colours most clearly is probably a survival advantage.

A

multi-coloured sunset over the Firth of Forth in Scotland.

When the air is clear the sunset will appear yellow, because the light from the sun has passed a long distance through air and some of the blue light has been scattered away. If the air is polluted with small particles, natural or otherwise, the sunset will be more red. Sunsets over the sea may also be orange, due to salt particles in the air, which are effective Tyndall scatterers. The sky around the sun is seen reddened, as well as the light coming directly from the sun. This is because all light is scattered relatively well through small angles--but blue light is then more likely to be scattered twice or more over the greater distances, leaving the yellow, red and orange colours.

A blue

haze over the mountains of Les Vosges in France.

Clouds and dust haze appear white because they consist of particles larger than the wavelengths of light, which scatter all wavelengths equally (Mie scattering). But sometimes there might be other particles in the air that are much smaller. Some mountainous regions are famous for their blue haze. Aerosols of terpenes from the vegetation react with ozone in the atmosphere to form small particles about 200 nm across, and these particles scatter the blue light. A forest fire or volcanic eruption may occasionally fill the atmosphere with fine particles of 500-800 nm across, being the right size to scatter red light. This gives the opposite to the usual Tyndall effect, and may cause the moon to have a blue tinge since the red light has been scattered out. This is a very rare phenomenon--occurring literally once in a blue moon.

The Tyndall effect is responsible for some other blue coloration's in nature: such as blue eyes, the opalescence of some gem stones, and the colour in the blue jay's wing. The colours can vary according to the size of the scattering particles. When a fluid is near its critical temperature and pressure, tiny density fluctuations are responsible for a blue coloration known as critical opalescence. People have also copied these natural effects by making ornamental glasses impregnated with particles, to give the glass a blue sheen. But not all blue colouring in nature is caused by scattering. Light under the sea is blue because water absorbs longer wavelength of light through distances over about 20 metres. When viewed from the beach, the sea is also blue because it reflects the sky, of course. Some birds and butterflies get their blue colorations by diffraction effects.

Images sent back from the Viking Mars landers in 1977 and from Pathfinder in 1997 showed a red sky seen from the Martian surface. This was due to red iron-rich dusts thrown up in the dust storms occurring from time to time on Mars. The colour of the Mars sky will change according to weather conditions. It should be blue when there have been no recent storms, but it will be darker than the earth's daytime sky because of Mars' thinner atmosphere.